Saving Poros

June 26th, 2023

People vs industrial fish farming in Greece

By Francesco De Augustinis (one-earth.it)

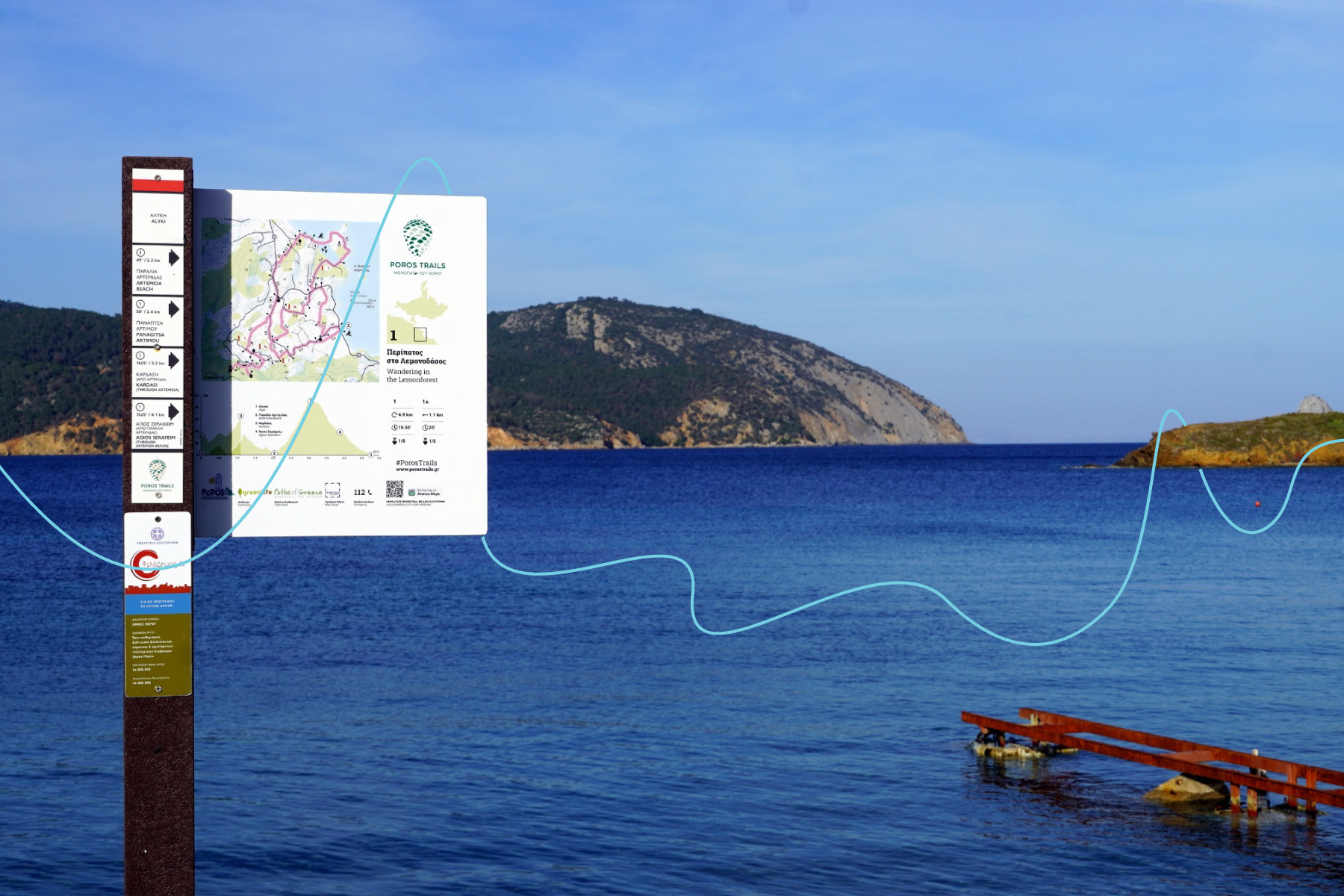

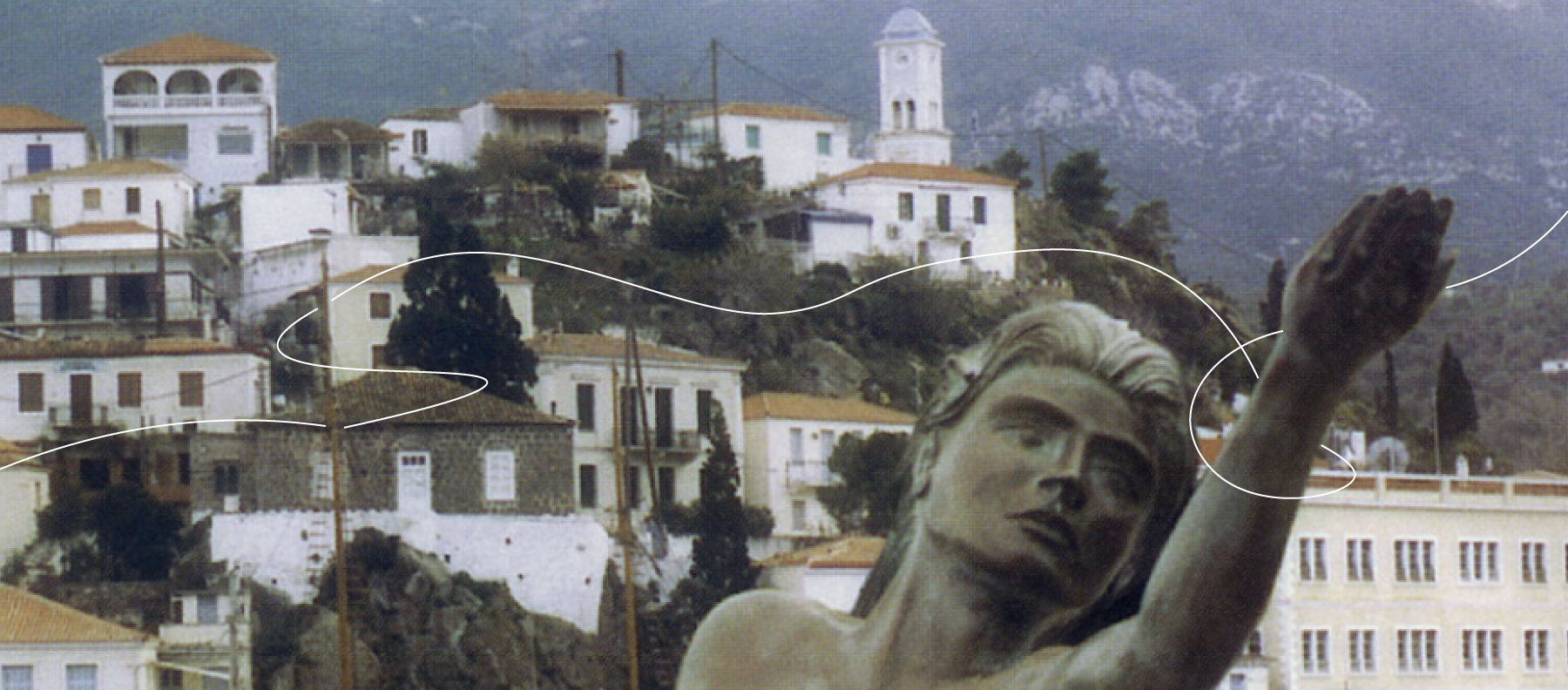

Poros is a small island in the Saronic Gulf, Greece, an hour fast ferry ride from Athens. A clock tower standing out among small white houses is the symbol of the main town on the island, settled in the southern end. The rest of the territory is almost completely unspoiled: woods, archaeological areas, bays surrounding pristine waters and rocky coasts where only goats can walk.

Paradoxically, it is precisely the pristine nature of Poros that is marking its future: the absence of large production or tourist activities was considered by the Greek authorities a criterion for including the island in a list of allocated zones for the expansion of industrial fish farming. This is a project that could become a reality in the next few months, triggering widespread protests in the local community.

“Aquaculture has been developing in Greece, with few exceptions, in areas where no other activities were there,” Filippos Petridis, director at Ambio, a consulting company involved in marine spatial planning in Greece and the entity that produced the environmental impact study for the project, tells us. “Unfortunately not all of Greece is a tourist paradise: some areas are benefiting from tourism, and they have had such a dramatic expansion in the last few decades; some others are not within the scope of people investing in tourism.” According to Petridis, aquaculture is much needed in these territories: “No one wants to go there and build Hilton hotels or major resorts in order to subsidize the local economy,” he claims.

On the other side, the inhabitants of Poros, almost all making a living out of small-to-medium scale tourism services, think differently. “They should do it elsewhere,” says Ioannis Dimitriadis, Mayor of Poros, “in an area where there is not a community of 3,000 residents all opposed to fish farming and where almost all are making a living from activities that will inevitably be compromised.”

A plan for fish farms

Marine aquaculture in Greek coastal waters was introduced in the early 1980s. The main productions are euryhaline finfish species, especially Mediterranean sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata), which is also marketed under the names Branzino and Dorade. According to the Hellenic Aquaculture Producers Organization, in 2021 Greek annual production of Mediterranean aquaculture fish reached 131,000 tons, with an estimated value of €636 million.

In the early 2010s the Greek government laid out a plan to increase production to 235,000 tons by 2030 and in 2011 identified 25 so-called “Areas of Organized Development of Aquaculture Activities.” Poros, where four farms already operate, is on the list: the plan is to devote 25 percent of the island’s coastline to aquaculture development, expanding the current area 28 times to 270 hectares (667 acres). According to the plan, annual production in Poros will increase from the current 1,147 tons to 8,831 tons in 5 years.

“The natural wealth of the island is the reason tourists come here, this natural environment, this coastal area, it was all untouched until the emergence of the fish farms,” Dimitriadis tells us. We meet the mayor in a municipal building, the facade of which boasts several banners displaying slogans against fish farms. The mayor has just attended a meeting of the Committee for Saving Poros, a group of residents who oppose the expansion of the farms, including representatives of trade, tourist and fishing associations, the clergy and ordinary concerned citizens.

According to a study on sustainable tourism and destination management, in 2015 Poros had a 4,000-bed capacity, 54,000 overnight stays, and a full 80% of the workforce was engaged in services directly or indirectly related to tourism. The mayor highlights that the island is also a favorite destination for boat travelers: “In 2022 the port of Poros recorded the arrivals of 18,000 private boats,” he says. “It is clearly a yachting destination and this coastline really is Poros’ principal asset when it comes to tourism.”

What kind of development for Poros?

A tour of the island is all it takes to meet several citizens angry with the fish farm expansion project, most of them concerned for the potential impact on tourist activities.

“When the marine environment is degraded, and on the one quarter of the island that is covered with pine trees they are allowed to do industrial fish farming, tourists will inevitably stop coming to enjoy the clean water and pine forest,” says Andreas Kaikas, a member of the local tourist committee, sitting inside his restaurant, a white wooden structure overlooking the sea. “So, 80 percent of the residents now working in tourism will have to turn to other jobs, which unfortunately is not an option on the island,” says Kaikas.

Katerina Sakelliou owns Odyssey Farm, an “eco-glamping” campsite focused on sustainability, with stylish tents, stone houses and a wooden cottage by the sea. “I have been involved in tourism for the last 40 years,” Sakelliou tells us, as we walk among rows and rows of freshly pruned olive trees. “I remember we were told that fish farms would provide a lot of work and create economic benefits for everyone,” she says. “Time has shown that the current farms employ very few local people and have in fact brought only contamination and damage to the environment.”

To date about 15 people work on Poros fish farms. According to the industry, in all of Greece in 2021 3,900 people were employed in the industry, including permanent and seasonal staff. This averages out to 3.9 people working in each of Greece’s 989 operating farms (including 283 marine fish farms and 460 shellfish farms).

“I believe it’s wrong to say that we need fish farming for the development of the region, as it is already developed around tourism,” says Sakelliou, who is also a member of Ec(h)o, a private initiative for the promotion of sustainable tourism in the area. “That’s exactly the reason we started an effort with our team so that the tourism that already exists could move in a sustainable direction, one that will help the environment and the overall quality of the area in general. Fish farms certainly do not help with this.”

Fish farming in pristine waters

The sunlight filtering through the clear water hits the Posidonia meadow, reflecting off the green and healthy seagrass waving on the seafloor. We are taking underwater images in the northern area of the island where, if the plan is approved, dozens and dozens of industrial fish farms will be settled. A few minutes later, the scenario becomes very different as we move into a bay a few miles ahead, where a fish farm is already operating. The seabed is lifeless, a gray floor with no sign of Posidonia or any other life: here and there we see only abandoned tires, remains of a former anchoring system for the cages.

The poor condition of the seabed around industrial fish farms is due to the release of huge organic loads, mostly animal feces, dead fish, and uneaten feeds: “An aquaculture business that produces 1,000 tons of fish uses 2,000 tons of feed,” Miguel Rodilla, a researcher at the Polytechnic University of Valencia who has for years been monitoring the seabed around fish farms in Spain, tells us. “Between 10 and 20 percent of that is lost to the environment,” he says.

According to Rodilla, in this kind of fish farm formaldehyde and antibiotics are also regularly released into the water, to keep the spread of diseases under control. “Certain chemicals are unavoidable for treating parasites,” Rodilla tells us. “Formaldehyde is a human carcinogen, but entire cages are given formaldehyde baths, since the substance does not affect the fish and eliminates the parasites.”

According to estimates based on environmental impact studies published by Ambio, after the expansion the farms in Poros would collectively release at least an average of 16 tons of organic waste into the sea every single day.

This calculation does not take into account a serious risk of illegal practices: As a former employee of Avramar, the biggest aquaculture company in Greece, which also owns the farms in Poros, reveals to us, “They need to produce more fish, so they used to put more tons than the amount licensed.” The former employee, who had been working in several farms belonging to the company until a few months ago, asks us to protect his identity, fearing retaliation. “In a cage licensed for 80,000 fish, they might put up to 120,000, so the areawould be overloaded,” he says.

The whistleblower also claims to have witnessed illegal practices such as the overuse of formaldehyde and the disposal of dead fish in the sea: “They dropped them on the seabed. And the dead fish meant that they were sick fish, and the fish outside of the cages ate them.” He further maintains that any inspection by authorities was pre-announced, so no irregularities were ever found, and says that safety measures for workers were also often disregarded: “That’s why we had a lot of accidents in sea farming. Some divers have died, and one was recently entangled in the net.”

In January 2023 trade unionists protested working conditions at aquaculture facilities in Greece, a few days after a worker at an Avramar farm in Dorida, central Greece, suffered a serious accident. In September 2022 two workers were killed in an accident at a fish farm in Parga, while – according to the trade union PAME – between 2012 and 2018 four divers died in as many occupational accidents on fish farms.

Christos Loverdos Stelakatos, a former worker for Andromeda, a company that became part of Avramar, has also publicly exposed through social media the same irregularities in the fish farms where he used to work in Igoumenitsa, Western Greece. “The main toxin used is formaldehyde, they use it by the ton,” he tells us when we meet him at his house. “And because they want to increase their profits, they increase the number of the fish in each cage, so this increases the number of parasites, bacteria, and diseases.”

Loverdos Stelakatos also exposes the lack of security measures for the workers: “They do not respect safety rules,” he says. “If you don’t provide any security measures to your workers or to your divers, that is your responsibility, not the responsibility of the diver.”

Avramar declined to comment on the allegations made by the former workers.

According to Filippos Petridis, Ambio’s chairman, “aquaculture is monitored by a huge number of Greek authorities.” In an interview, he acknowledged that “in previous years” people working in the farms “were not well trained and were coming from different backgrounds with different understanding of their own business and of the environment, which brought some adverse effects.” He went on to claim that the company has recently entered a more mature phase, when “we realized the complexity of our activity, the effect we have on the environment.”

The long hand of finance

The plan for the expansion of fish farms in Greece dates back to 2011, but to date only eight of the 25 sites have been definitively approved. In recent months, however, the process has accelerated: in February 2023 the most recent area was approved in the Echinades Islets & Etoloakarnania, in Western Greece, despite widespread protests among the local population.

“There is no growth potential if we remain at 130,000 tons production,” says Apostolos Touralias, chairman of the Hellenic Aquaculture Producers Organization and country manager of Avramar Greece. “Turkish fish farmers are expected to increase their production from 50,000 tons to over 300,000 tons in 2023 and will reportedly approach 350,000 tons in 2024.”

In April 2022, at the Congress on Greek Aquaculture, a conference organized by Ambio with the support of the Hellenic Aquaculture Producers Organization, Touralias asked the government to speed up the approval: “Planning must be completed. And this must be done now,” he said.

The reason behind the acceleration in the expansion of fish farms in Greece is likely the arrival in recent years of huge amounts of foreign capital, with private equity funds that have taken over major Greek companies.

Avramar is itself a multinational company based in Spain that owns 70 percent of Greek’s production of farmed fish. With a turnover of €450 million and 100,000 tons produced in 2022, Avramar is the leading producer of farmed fish in Europe. The company is owned by two private equity funds, Amerra Capital Management, based in New York, and Mubadala, a sovereign wealth fund of the United Arab Emirates, that since 2016 has taken over the Greek companies Andromeda, Nireus, and Selonda.

“We know that the salmon farming industry, which also started in the 80s and 90s, today produces 2.5 million tons,” said Thor Arne Talseth, Chief Executive Officer of Avramar and former head of private equity for Amerra, speaking at the same 2022 conference. “The combined Mediterranean aquaculture production is around 500,000 tons. So for us, as an investor, we saw that aquaculture is an industry with strong tailwinds, and at the same time the Greek aquaculture industry and the Mediterranean aquaculture industry were not using their full potential.”

Talseth confirmed Avramar’s urgent need for approval of the fish farms expansion plan in Greece: “To support our investments and future growth in terms of significant competition from Turkey,” he said, “it is necessary to implement the regulatory regime that we are all talking about, the special regime, the POAY [the Plan for Organized Aquaculture Development Areas].”

In December 2022 Devlin Kuyek, a researcher for Grain, a Spanish-based NGO, published a report about the growing investments by private equity funds in the aquaculture industry in Spain and Greece. According to Kuyek, the scope of these investments is likely to increase the production capacity, in order to sell their assets in a span of a few years. “They don’t necessarily seek a profit on a yearly basis, they are looking at profiting when they exit,” Kuyek tells us in an online conversation. “So they want to make sure that they can produce as much as possible. What that means for the environment or the impact on employment in other local industries, that’s not something they care about.”

Different countries, different rules

The Avramar group is based in Valencia, Spain, but the bulk of production is in Greece, where it operates nine hatcheries, 62 farms, and several processing centers. A simple visit to the farms in Spain and Greece allows us to understand why the group’s interest is concentrated on the Greek coasts.

“The farm must be at least 30 meters deep,” Eduardo Soler, from the sustainability team of Avramar Spain, tells us. We are talking on a small boat, while we visit a sea bass and sea bream farm in Burriana, a few kilometers North of Valencia, Spain. The cages are settled about 4 miles off the coast, in open sea, very exposed to currents and storms: “The closest farm to the coast that we have [in Spain] is 1.5 miles off, it is located in La Vila Joiosa,” says Soler.

The scenario is very different when we visit the Avramar farms in Poros, or in the nearby towns of Methana and Epidaurus: the cages are a few meters away from the shoreline and are sheltered inside small bays, in an area of sea surrounded by mountains that looks a lot like a lake due to the lack of currents. According to a study of the impact of fish farming on the Greek marine environment, most of the farms in Greece are located between 50 and 200 meters from the coast.

Farms located in sheltered areas and close to the coast make it possible to reduce production costs like transportation, and the risks associated with currents and storms. In 2020, 90 percent of the Avramar farm in Burriana was destroyed by the storm Gloria. On the other hand, the concentration of farms near the coast in Greece triggers criticism about the impact on the environment – due to the lack of water recirculation, among other things – and on tourism.

“I am concerned about whether the farms harm the environment and the marine quality of the region,” Tasos Ladas, Chairman of the Professional Fishermen’s Association of Troizinia-Methana, tells us, standing in his small boat beside a sea bream fish farm in Poros. Ladas is a fisherman, but during the summer he takes tourists to visit the island. “They occupy areas of the sea, our bays and other spots in this stunning area, which we then cannot use as ports for boats, for swimming, or just for the enjoyment and recreation of tourists,” he tells us.

Sustainability or neo-colonialism?

Greece will receive €364 million from the European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund 2021-2027 and 25 percent of these funds will be invested in aquaculture. The European Union considers the development of aquaculture as a strategy toward a more sustainable food system, which, according to VirginijusSinkevičius, EU Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries, will “support Greece’s green and digital transition.”

On Oct 2, 2020, the Poros Municipal Council voted unanimously against the establishment of industrial-scale fish farms and the Poros community describes aquaculture in Greece as an example of modern-day colonialism. “The State comes with legal procedures, overriding the will of the people and the powers of the elected bodies, forcing something that is completely against the wishes of the local community,” says Mayor Dimitriadis. This plan “will establish and give an administrator role over a large part of the territory to a private company. If we don’t call this a colonial model, I don’t know what we would call it,” says Dimitiriadis.

About Francesco De Augustinis

An independent journalist and documentarist, Francesco De Augustinis, has 10+ years of experience in food and environmental issues. In 2019, Francesco founded the independent media project on sustainability, One-Earth.it. Since 2021, Francesco has worked on projects about industrial fish farming around Europe, Africa, and South America. His full bio can be found here.

Featured image by Bernhard Lang

Katheti has compiled a wealth of information about the issue of fish farming, Poros, case studies from around Greece and the world, the POAY and Avramar. Please check out our Fish Farm Resources site.